Bogdana Pivnenko: “The most important thing for students is to be influenced by teachers who ignite the passion

Bogdana Pivnenko is a violinist, Honored Artist of Ukraine, laureate of international competitions, and participant in numerous international festivals (Berliner Festspiele MaerzMusik, Ruhr/Germany, Vienna/Austria, Grand Prix, “Warsaw Autumn,” Krakow, “Nostalgie”/Poland, and others), as well as “Days of Ukrainian Culture” (Paris, Vienna, Berlin). For many years, she has been touring Spain, France, Germany, Austria, Japan, China, and the United States. She has participated in premieres of works by contemporary Ukrainian composers.

After the start of the full-scale war in Ukraine, Bogdana and her son moved to England under the Homes for Ukraine scheme, but she continues to actively tour European countries, giving concerts and teaching students who found themselves outside Ukraine. Bogdana is a Cherwell College Fellow and participates in cultural events organised by the college. To learn more about how the violinist’s life has changed since the start of the full-scale war in Ukraine, her impressions of Oxford and British education, read the interview.

Bogdana, how has your concert activity changed since the start of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine?

One could say that there has been a significant increase in interest in Ukraine, Ukrainian culture, and Ukrainian music. It’s unfortunate that this is due to such a dreadful event, the war, which is a real catastrophe for our country.

Most people had no idea what Ukraine was like, they had no clue about its rich culture and the many outstanding composers it has. This year, wherever I had the opportunity to perform, I saw a tremendous interest from the audience. And often, after the concerts, many people from different countries – Italy, Switzerland, UK, and Germany – would come up and ask, “Why have we never heard this music on the radio?” They know Tchaikovsky, Shostakovich, and Rachmaninoff, but they are unfamiliar with Skoryk and Stankovych. Only recently has Silvestrov, a Ukrainian composer, started to be heard. Interestingly, the world always compares and says that Lyatoshynsky is the Ukrainian Shostakovich. However, the truth is that Lyatoshynsky’s Sonata was composed in 1924, before Shostakovich wrote all his significant works. Perhaps it is our mission to introduce our culture to the world and talk about it.

At the end of November, the “Ukrainian Modernism” exhibition opened in Madrid at the Thyssen Museum, owned by a baroness who is still alive. The works of our artists from Kharkiv and Kyiv were presented, but during the Soviet period, their works were always presented as Russian modernism. Now it turns out that it is Ukrainian modernism! During the official opening of this impressive exhibition, when the baroness addressed the press, she said that this exhibition shows that Ukraine has a tremendous culture. Most European countries can only dream of having such achievements in art, music, and science. We have constantly underestimated ourselves and failed to promote our achievements because during Soviet times, everything was considered Russian or Soviet. But now we need to shout it out at every step, not be afraid to talk about it, because it changes the country’s image completely. Ukraine is an entirely European country with an extraordinary culture, impressive educational and creative potential.

Is this the message that you and other Ukrainian artists are delivering to the world, to Europe?

Yes, the role of art and artists is crucial in conveying the message that we are a cultural country with enormous traditions, a colossal school of arts, music, and science.

You perform quite frequently here in Oxford. What are your impressions of the city and the audience?

Oxford is a city with rich traditions. It is small but very atmospheric. Moreover, it attracts incredibly intelligent and educated people, mostly young individuals who will shape the future of the world. It’s fantastic that we have something to tell and show them, something that will capture their interest. Especially considering that Britain is a clear ally of Ukraine in the war and provides significant support to Ukrainians.

Continuing the topic of the future and educated individuals, what do you think the interaction between humans and artificial intelligence will be like?

They say that writing activities are easier for artificial intelligence because there is a vast database available. However, I find it difficult to imagine artificial intelligence dancing ballet, playing the violin, or the piano. These activities require talent and being human.

In theory, artificial intelligence can generate anything.

But artificial intelligence selects from existing options, analyses what humans have already done. For example, playing the violin is so versatile that it’s impossible to provide a recipe for it… When my son asked a GPT chatbot, “How do I learn to play the violin?” he received general advice like finding a teacher and a list of literature. However, anything related to touch and feelings is probably still challenging for artificial intelligence in this field because it requires being human. That’s the strength of creative professions – they influence people’s emotions.

What cultural component, in your opinion, should general education necessarily include?

I really like the education system in England, where children have music lessons, and they take an instrument and try to play it. And this musical interaction is a tradition that Ukraine lacks. We have specialised music schools or art schools where they teach professional playing. However, in general schools, this topic is neglected because they only talk about music. But music should be played, not just talked about. That’s why I like the system where you can try one instrument this year and another the next year. The same can be said about art – children should be given a chance to personally try everything.

Your sixteen-year-old son has been studying at Cherwell College for several months. What are your impressions of this experience?

I believe that we were very lucky to have the opportunity to enroll in the college. The public school system relies on the fact that a child must have enough motivation to resist all temptations and be very diligent in studying. No one cares about your results; your results matter only to you, and teachers can only give advice. In contrast, Cherwell College focuses on results. They genuinely care about helping the child realise their abilities and get into the university they want. They are not indifferent. It’s not just a case of “you graduated, and we forgot your name”; they want you to achieve your goals. And this is the fundamental difference in approaches. I can see from Bogdan that he is not willing to exchange Cherwell College for a public school in England where he previously studied, or for a gymnasium in Bern, Switzerland, or for a school in Ukraine. And this is a significant indicator. My boss always said that the public votes with their feet. And children are the same; they have their own point of view. I listen to my son’s impressions when he talks about brilliant history lectures, for example, and I can feel how interested he is in the lecturer. When I talk to the English language teacher, I can sense how much she cares about how Bogdan will perform in his tests and what results he will achieve. And this concern is priceless; it’s the most important thing.

How did you choose the college?

It happened completely by chance because Cherwell College was the organizer of the Ukrainian Cultural Weeks in Oxford, which took place in late September-early October, and that’s where we met Helen (the college’s vice principal). It also happened that there was an opportunity to observe the college’s work for two months, and I was extremely impressed by the approach, which differs greatly from our system. There is more variety here; they encourage children to be creative, to engage in their own research on each topic. They encourage them to think, analyse, and motivate them, and that is very valuable.

Even in the most challenging situations, Helen infects others with her optimism and confidence that everything will be okay. Talking to her, you understand that everything will be resolved, all problems will be solved. She has tremendous patience with teenagers, understanding, and a sense of them. And I see with my own child that he really enjoys being here; he feels very comfortable. A few months ago, he was like a hedgehog – very withdrawn due to the war and change of residence. But now I see that he is gradually relaxing inside and feeling more comfortable. He understands that he is not on the battlefield but in a safe and supportive environment where he can relax and simply learn.

This year, the college traditionally participated in another cultural event called Oxfordshire Art Weeks, and your concert was part of the programme. Tell us about this experience.

Art Weeks is a fantastic event because the college gives all its students the opportunity to try themselves in art and showcase their talents. Nowadays, it’s much easier for teenagers to simply sit with their gadgets. When they step outside the confines of the gadget-centered world, they don’t know what to do with themselves. And art provides an opportunity to realise the abilities that are inherent in every person, which they may not even suspect because they haven’t had a chance to try. That’s why it’s a wonderful idea to give all these young people the opportunity to express themselves because they can discover unexpected talents that may eventually become their profession. In art, there is always room for growth; it knows no boundaries.

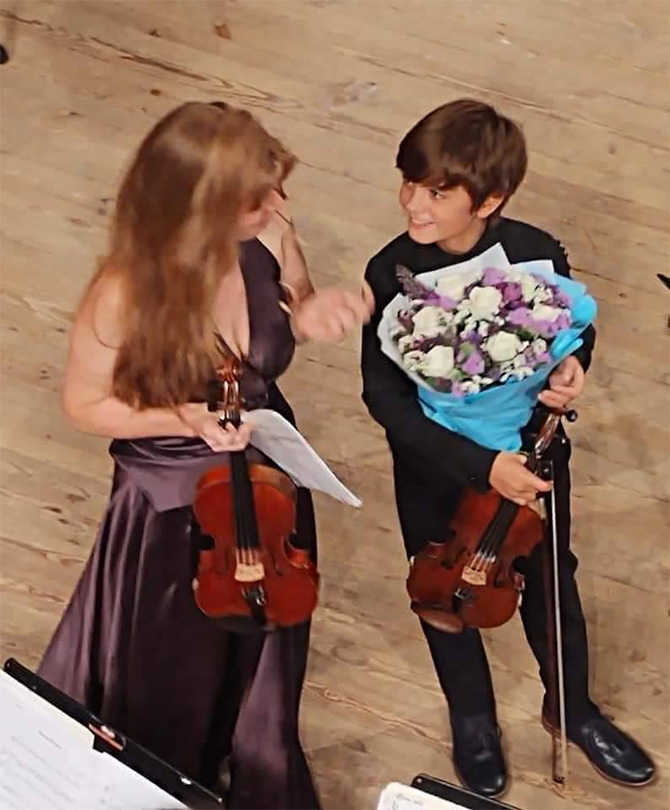

I performed for the first time with a special programme during the Art Weeks organised by Cherwell College. Together with my student, Kory Sheldunov, who is also currently in the UK, through a duet for two violins, we showed the audience the interaction between a teacher and a student and how it can transform in a beautiful musical dialogue. I believe the audience appreciated it, and it was a great concert.